How to Drown in America

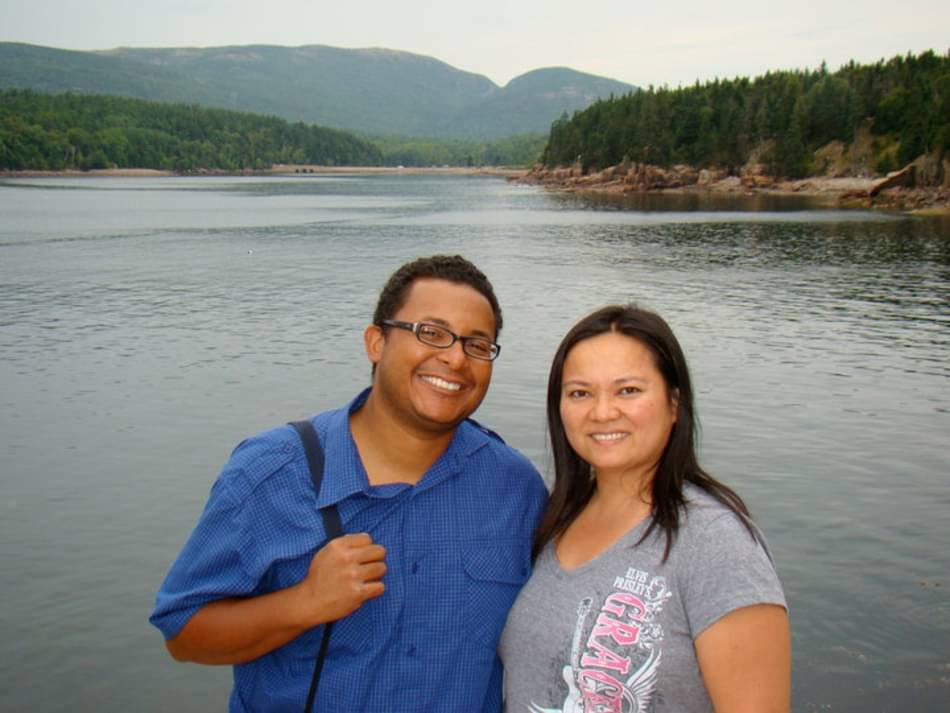

Grace Talusan and Alonso, 2011. © Grace Talusan.

Within our first six months of dating, my boyfriend and I almost died together.

In our early twenties, both far from home, Alonso and I met in graduate school in Southern California. We were starting new lives, remade in this new place, our past selves seemingly evaporating in the constant sunshine. Dreamy and full of endorphins, I glossed over our differences. What did geography, sociology, history, and economics matter in the face of our romance? We were in love. What even was race? I had grown up in New England and he was from the South, but here we were in Los Angeles, a place famous for the possibility of reinvention.

We didn’t think our pasts were relevant. So what if my Filipino, immigrant, physician parents could easily write checks to cover my private undergraduate tuition, living expenses, and a car while Alonso’s Black single mother—underpaid her entire working life—did not have the leeway in her budget to pay the fees for college admissions tests? Graduate school offered us a fresh beginning and our first taste of financial independence. We were awarded the same graduate school fellowship, meant to encourage more professors of color in the academy, and I believed this meant we were at the same starting line in the marathon of graduate school. Our paychecks were the same, which meant we were the same, a habit of thought I blame directly on American rhetoric that most of us belong to the middle class. And I’ve always wanted to belong.

During our first summer together, I was eager to introduce Alonso to my college pals back in New England. They invited us to join their annual canoe-and-camping trip in Maine and I jumped at the chance. I had not been invited before and I wanted to become the kind of person who spent more time outdoors in performance gear. (Spoiler alert: I was not invited again.) At first, Alonso hesitated, weakly, because he didn’t swim and this was an overnight river excursion. But I assured him he would be fine. After all, we weren’t swimming; we’d be canoeing. He agreed to the trip without letting on: The only time water touched his skin was in the shower; there had not been money, time, or motivation for swimming lessons. As for me, I had grown up with a swimming pool in my backyard. Almost every neighbor on my street and almost every friend I spent time with either had a pool or a waterfront vacation home on Cape Cod or in New Hampshire. I assumed that everyone at least knew how to float and doggy paddle because I had never been in a situation where someone couldn’t. It didn’t occur to me that some people had no idea what to do with their bodies in water. The limitations of my imagination and inexperience showed. What’s the worst that could happen?

Grace and Alonso. © Grace Talusan.

We drove north and showed up to the river adventure my friends had planned and, sure enough, Alonso was the only Black American in our group—and in the general vicinity—and I was the only Asian American, but I was used to that. I had grown up this way—being the only Asian person—and almost all of the time, I could melt into whiteness. Only when it was too late to turn back from this river journey did I understand how ignorant I was. How some stories we told about ourselves and the world we live in, as much as we wanted to believe them, were not true. No one uses the term, “melting pot,” anymore, but people said this word aloud around me all the time and I believed that if I continued being a good immigrant kid, America would reward me. I was not ready to discard this delusion in my early 20s. I still wanted to believe that race didn’t matter.

We were a half-hour into our river adventure, our canoe floating on the Saco River, when the first Confederate flag—attached by a metal pole to a canoe shared by two white men with crewcuts and sunburned noses—glided beside us. They were so close I could have touched their freckled arms. I saw Alonso brace himself, but no one said a word; the twangy music from the other canoe radio was the only sound. Alonso paused his paddling and the canoe with the flag sped ahead on the current.

That canoe turned out to be the first of many flying both the Stars and Stripes and the Stars and Bars. A few wives or girlfriends were along for the ride, but the canoes held mostly stiff young men with buzzed hair, reminding me of movies I’d seen featuring soldiers on R and R. Having grown up in Massachusetts, many miles north of the Mason-Dixon Line, I was confused by the sight of so many Confederate emblems on T-shirts, hats, and flags this far north in Union territory. My reference to Confederate flags was the flashy car on the “Dukes of Hazard” TV show. But to Alonso, a Black man from Kentucky, the symbol clearly warned: “You are not welcome here.”

After we were passed by a dozen or so canoes with Confederate flags attached to the front and coolers tied to the back, Alonso finally remarked, “I didn’t realize there were so many rednecks up North.”

“I think white supremacist is the preferred term,” I joked.

He sort-of laughed, “Ha!” Alonso was always on the lookout for what he’d learned to label “hillbillies and hicks,” a category of white person that he was taught to avoid. There was no reasoning with them. But still, I felt guilty, then annoyed. Why hadn’t my friends—my white friends—warned us that the river might host a floating parade of Confederate pride?

I knew the answer; as white people, after a lifetime of living in a society that insists race doesn’t matter, they probably did not notice. They did not need to pay attention because it didn’t endanger them. As an Asian American, I am in such close proximity to whiteness that I had only felt threatened by these symbols when I was next to my Black boyfriend. Now, the air changed every time a Confederate flag flew past us. Some of the men smiled tightly at us; others shook their heads, staring silently ahead to where they wanted to go: far away from us. We pretended not to see them, too.

My bumbling cheerfulness could usually get me out of any tense social situation, but I felt a deep sinking feeling in my body. Had I utterly miscalculated? My childhood in the late 70’s and early 80s was filled with rhetoric about how the American Dream was available to anyone who worked hard and wanted it enough, and how what really mattered was more than skin-deep, whether this skin was purple, blue, or green. We wanted to believe in meritocracy; we wanted to believe we belonged to the middle class. America was a story we told ourselves. America was an agreement. Even now, despite how much I’ve tried to learn, I am still finding out how being a Black American man is not the same lived experience as mine.

We coped the way we’d learned to manage as people of color in public spaces: pretend everything is fine. That night, we enjoyed the campfire hot dogs and sing-along. As we fell asleep in our tent, we listened to the sounds of the river at night: water lapping the shore, crickets, frogs, and birds.

The last morning of our trip was hot, the river shallow. Alonso and I hopped out of our canoes, threw our life jackets under the seats, and waded downriver. My friend Tim tied our canoe to his flotilla so we could wade unencumbered, hand in hand, through the water. I watched Tim disappear around a bend, walking several empty canoes as if they were a pack of dogs. We would catch up with our friends later.

Alonso and I had fallen far behind the flotilla, oblivious to anything but each other—including the river conditions. We dreamed aloud about all the places we wanted to travel together. The people and places we wanted to introduce each other to. The favorite foods we wanted each other to try. The dishes we would cook for one another. We walked and talked, conjuring our shared future and all of its beautiful possibilities. The moment before everything changed is still with me: the way the sunlight shone through the leaves of the trees that grew near the riverbank, the way the water cooled my legs, and the whistle of the Northern Bobwhite.

In real life, drowning is quieter than in the movies.

Suddenly, from still, knee-high water, the current shifted and I plunged into water so dark and cold that I couldn’t touch the bottom. It was as if I had stepped off the lip of a swimming pool into the deep end with a backpack full of stones. I sank sharply and ran out of air fast, shivering in the icy cold depths.

Luckily for me, years of swim lessons ignited me and, desperate for breath, I kicked and crawled towards the blue sky. My face cleared the water and I gulped oxygen, but almost immediately went under again, pushed down by a powerful, desperate force. The river current had also pushed Alonso into the deep water and—without a lifejacket, without swimming experience—he had nothing to hold onto, besides me. I remembered a warning from my swim class at the Y: Never get into the water with a drowning person. Throw them a safety ring or a life jacket. A drowning person could kill you. It’s instinct, the body fighting to survive.

Drowning transformed us into our most animal selves. We became strangers in the water and flailed like all the fish we had ever caught and collected in a pail, gasping helplessly until they died. I knew that I was in acute danger. Never before had I felt death come so close, so quickly, but there it was. Cold, dark, matter of fact.

Struggling to the surface while the current moved us downriver, I took another quick breath. Alonso grabbed me again and I sank, overpowered. I felt his desperation. There is no other way to describe this: He climbed me like a tree. I felt his sandals on my shoulders as he pushed off.

Floating helplessly above the dense mat of plants at the bottom of the river, my muscles too weak to fire, I had the clearest thought I’ve ever had: I will die today in this giant green room. I pitied my loved ones and the burden I would impose on them, this tragic story they would have to tell repeatedly in order to explain my sudden death. I would always be 25 years old.

I distracted myself with this thought, My immigrant parents are going to kill me for dying this way, but the delight of the joke was immediately erased by the realization that I would not laugh about it later. I wouldn’t have any more laters.

I had heard that before you die, your life flashes before you. I always thought that meant your past, but what I grieved were glimpses of my unlived future: I saw myself as an old woman with silver hair wrapped in a loose bun the way both of my grandmothers wore their hair. I saw a small yellow house with colorful wildflowers spilling over a white picket fence. I saw myself sitting at a kitchen table amidst children dropping cookie dough onto a sheet. A shelf of books with my name on the spine. Time was fast and slow at the same time. This is it. This is how it ends.

And then, I was in a canoe staring at the back of a twentysomething man sweating through a faded T-shirt. In another canoe next to us, Alonso sat shaking behind another stranger. Two more men swam behind us. Our rescuers looked much like the men we’d seen earlier; I imagined they belonged to the same off-duty platoon. They were silent and serious as they paddled us to shore, where their campsite flew the biggest Confederate flag I’d seen. Or maybe my eyes saw the flag out of proportion and I perceived it to be as big as the sky. The flag flew on a flagpole, the kind of metal pole that is permanently in front of schools and government buildings, which confused me because we were on a temporary campsite on a riverbank.

Our rescuers helped us out of the canoes and onto the beach where they’d camped. One man asked us a single question: “Do you need medical attention?” I glanced at Alonso and shook my head, No.

The men’s girlfriends flitted around them, relieved. We were disoriented and couldn’t follow their conversations, but one of the women looked up at us and said, “They’re in shock,” then led us to a log where we sat, shivering with adrenalin. Alonso and I faced each other. He held both of my hands and asked if we could recite The Lord’s Prayer aloud together. I was shaking so much that my voice vibrated the prayer that, as a Catholic, I had known before I could even read. I felt as if I’d just awoken from the nightmare of another person’s life, which was left behind in the water. I felt newly born, full of gratitude that I was still here, alive.

The people on the beach kept their distance, watching us as the flag flew above them. Soon—no more than twenty minutes later—my friend Tim circled back to find us, then loaded us into his canoe. We were still shaking so much we could barely form sentences. I think our rescuers told him the story. They had an ease between them, white man to white man. Is it ugly for me to notice? The thing about racism is that it's hard to know the difference between a racist and someone who is just a jerk. As Alonso tells me, “If politics is who gets what, when, and how, then to whom can one be a jerk? Racism obscures itself. It clouds reality.”

We turned to offer a weak “thank you” to the strangers as Tim paddled us off. What is the proper etiquette when someone saves your life?

We made it downriver, exited the canoes, and went on with our lives. Eventually, Alonso and I married. But first, he forgave me for this ill-conceived trip, and I absolved him for using my body as a buoy. He was drowning, he explained, but he fought instinct, waiting until he saw me take a breath before he reached for me again. While I was underwater, certain I would die, abandoned and alone in the Saco River, he spotted the flash of red from the flag, the symbol of hate our only possible rescue, and yelled until the people below the flag saw us. He did not despair and accept his fate the way I had. He would not give up so easily and used whatever breath he had to scream for help. Again, our experiences were not the same.

Another thing about drowning: It is incredibly dangerous to attempt to save people in the water. Drowning while attempting to help someone—much less two people—is so common that there’s a name for it: AVIR syndrome, for Accidental Victim Instead of Rescuer. The American Red Cross, who has trained millions of Americans to swim since 1922 through its aquatic safety programs, even has a catchy slogan on an educational handout about responding to water emergencies, “Reach or Throw, Don’t Go.” Clearly geared towards children, a smiling blue whale character at the top of the page, one of the bulleted key points includes, “We can help someone who is having trouble in the water without getting wet.” The handout defines a drowning victim as “a person showing behavior that includes struggling at the surface for 20 to 60 seconds before submerging.” That was us.

It’s hard for me to recall exactly what happened when the men rescued us and placed us in their canoes. I had been struggling in the water for long minutes by then, low on oxygen and exerting myself to swim to the surface before sliding back down again. I was also scared to death. But as I read the American Red Cross handout, flashes of what I think are memories return: White men in canoes. A paddle held out to me. Maybe a rope? I don’t know how I got into their canoe—did two men pull me in by the arms or did I somehow lift myself over the boat’s edge and heave my body into the canoe? I was in shock. It was traumatic. The episode is not a memory, but mirrored shards reflecting images of green water, blue sky, and men with serious expressions on their faces, but only if the sun hits the glass just right. I can’t hold on to the memory even though the evidence that it happened—we lived and I am writing this essay—is irrefutable. They saved us from drowning.

Growing up, I heard a myriad of complaints from white people in the homogenous New England small town that I grew up in about minorities, immigrants, and Black people. How we ask for too much; how we should be happy with what we’ve got; how we take too much—spaces in elite college admissions and professional sports teams and in book publishing and in the movies—there’s nothing left for hard-working white people anymore. Where are the opportunities for white people amidst reverse racism, affirmative action, and diversity initiatives? And why couldn’t we make up our minds about what we wanted to be called? They didn’t mean any offense by the term “Oriental.”

Was it possible that our racial identities and the materiality of their Confederate flag dissolved during those intense moments when the men decided to get into their canoes and paddle towards us? Those men risked their lives for ours, but I never even learned their names. Then again, they didn’t learn ours.

Do those folks ever think about that harrowing summer day, or have we been forgotten? If they still tell our story, do they describe us as “the Black man and the Asian woman”? When asked recently about the day we almost drowned, the folks on the river trip (even Tim himself) have no memory of it at all. It makes sense. They probably never knew what happened to us because we couldn’t talk about it that day, and still, decades later, we never wanted to bring it up.

If you were on the Saco River in 1997, do you remember us? I remember you when I see the sun shine brightly through green leaves into a body of water. I want to tell you that Alonso and I eventually married. We love each other; we love our lives; we finally belong. We try our best to work against the ways that racism and other oppressive systems flatten us.

But this desire to update our rescuers is misguided, I realize, and reveals a fundamental belief of mine: that I need to justify the value of my life. Maybe this proves just how American I’ve become, that this toxic thought has wormed its way into me. All life has value, no? And yet, when I went to vote during the first election after the movement began for Black Lives Matter, I noticed that my polling site hung a banner that read, “All Lives Matter,” a seemingly innocuous phrase for its obviousness and yet, a motto created by white America to acknowledge white America, as if they'd ever been forgotten. I felt discouraged as I voted and noticed how, again, my husband and I were the only non-white people in the space. Later, I was angry as I recalled that I have the right to vote in a polling place without political signage. If I am American enough to decode subtext, I am also versed in complaint. I was proud of myself for bringing this to the attention of people who could make a difference and eventually, some years later, the city council voted to move the polling place elsewhere because the site—even on election days—refused to take down their banner.

If you were on the Saco River about a month before Princess Diana and Mother Teresa died, do you remember us? We didn’t die that summer because of you. Even if we’ve been forgotten and you’ve never thought again about that day on the river, thank you.

Grace Talusan teaches writing at Brown University and is on the board of the National Book Critics Circle. She is the author of The Body Papers, which won the Restless Books Prize for New Immigrant Writing and the Massachusetts Book Award in Nonfiction.