Coda

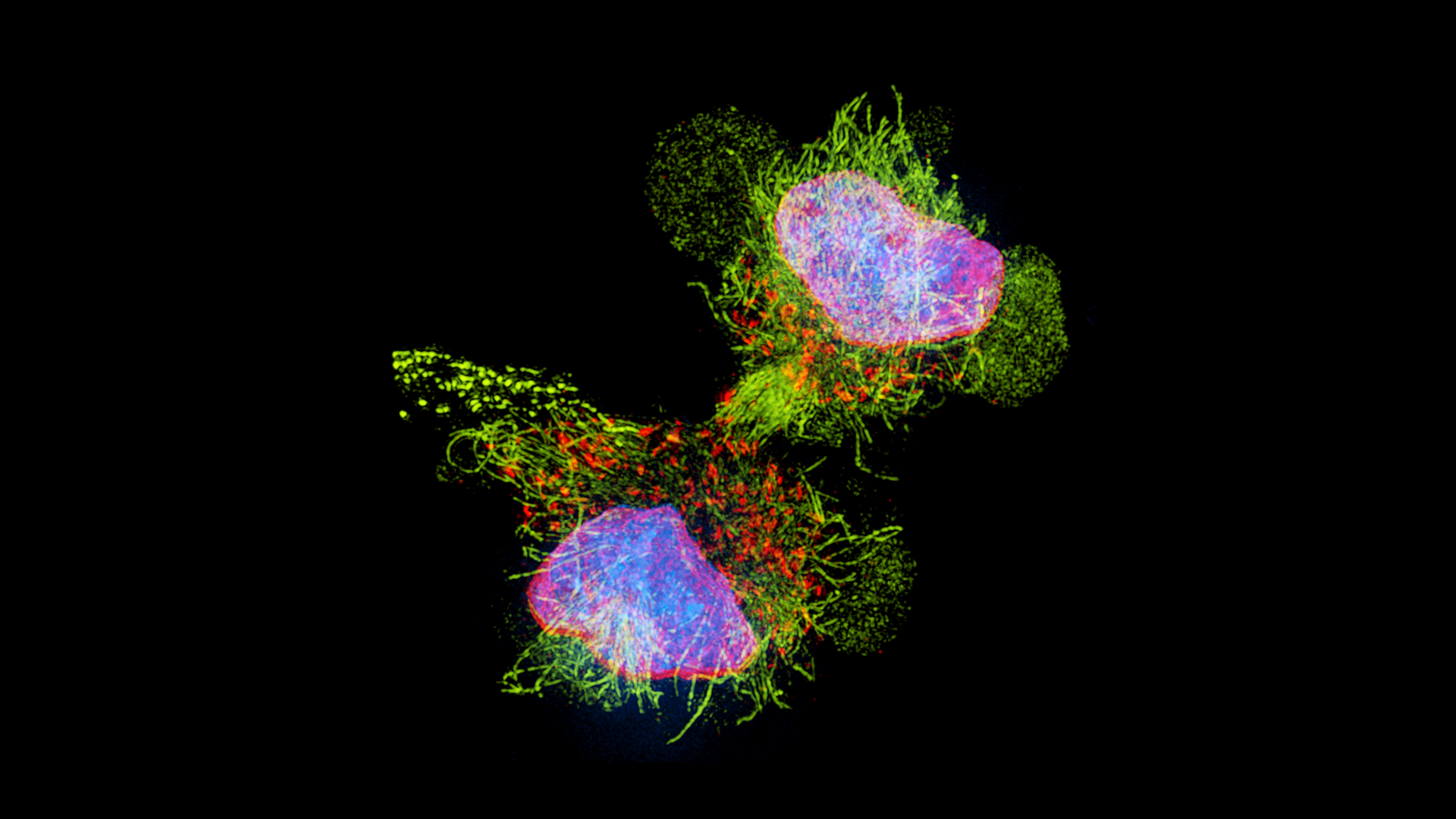

“Cell division, 3D-structured micrograph.” Licensed through Science Photo Library. 2024.

When it happened, I suddenly recalled the expression split in two.

It was six in the morning and I had been laboring for twelve hours. The sun was almost up. We had the youngest blondest night nurse who was sweet like I imagine angels must be. You’re doing incredible, she would tell me as she pulled her hand out from inside me and announced how wide I had become. Six then eight, then nine, then nine and a half. I had Marta on one side and our doula on the other. We would be calm, or at least recovering, and I might gasp, exhale and say how long or how strong the last one had been; the lights were dimmed, the bathroom door ajar, a row of windows curtainless before the night sky, my feet bare and still trembling, and then the next one would start to form inside, rolling me up just as it stretched me to the corners of the room. It was not pain any more than it was euphoria. It permeated my body, my vision, the space between my self and everything else. So much so that there were moments when I was sure I could talk to god. And I don’t even believe in him. But there was an other-worldliness to my laboring that made it seem like he very well could exist, like that would be the least fantastical of all the glorious and mad things that were happening between me and the absoluteness of pain. But then the baby came and I was split in two and the baby ate whatever there was of god in the room and now he definitely doesn’t exist.

Split in two is redundant. If you split anything, you create two. Imagine a fruit. An apple maybe. It’s been dropped from a good height and on impact breaks into halves. To make new life the cells first divide. Marta told me that when she saw our daughter come out of me part of me came out with her. It was not pretty. I still wish I had seen it.

Two weeks to the day after the birth, we had an election. There was a man on one side and a woman on the other. He was tall and spoke in simple sentences. She was more or less his age and perhaps they could have been a couple in some other universe, one in which he and she grew up to be ordinary people, like you and I are, and met and fell in love—he attracted to her decisive personality and great hair, she to his height and refusal to ever back down—and, in a world like that, one in which they would never realize their potential, the potential in them to galvanize all that is mean and ugly about the rest of us living in this country where we are forever and always choosing between just two options, neither always all that good, but in a world like that, they might have just been happy, or at least content, to marry and have kids and watch their kids grow and then retire and eventually die.

I was on her side, obviously. And the night the election results came in, I was in the same spot in our bed where I had been most of every day since the birth, since my splitting in two. I nursed her, our new little one—just seven pounds, mouth a whirlpool, hands like crocuses breaking earth—and my nipples cracked and bled. At night they leaked milk into my sleeping shirt and I’d wake sticky and blurry-eyed to feed her more. But I was blissful—full of bliss. Because there is a rush of hormones after birth and then waves of endorphins for weeks after that: each time I looked at her, fed her, smelled her, thought of her. It seemed that nothing could ever go wrong. It appeared that the world was perfectly planned. Everything made sense and had its place.

But I was also blissful because I believed things could only keep getting better. Everything I read told me that my candidate would win. My newspaper predicted her with ninety percent surety. Friends were explaining to their little girls how tomorrow they would wake up to—finally—a woman in the White House.

And so there Marta and I were, in the bed, with this tiny one who had just weeks before been part of me. I think she’d just fallen asleep, though she could have been awake and feeding, and we were watching the election returns. Indiana and Kentucky for him. Vermont for her. West Virginia, South Carolina, Alabama: his. Connecticut and Delaware: hers. It was around nine that I started to realize this country, my country, might actually choose him. But I thought if I closed my eyes maybe I would wake later to find that everything was as it should be, as I wanted it to be. My baby was already asleep and so I slept, too. When she woke me up at three to feed, he had won Iowa and Florida, and an hour later when she conceded I realized that we’d been split, too.

I also realized that we’ve always been split.

There was an interactive graphic put up by the Wall Street Journal sometime before the election that showed the Facebook feeds of conservatives and liberals. You could search by issue. I searched the shooting at Orlando’s Pulse nightclub and the liberal feeds were all about safe spaces and hate crimes and queer and Latinx culture and what the gay club has meant to those of us who still are not able to show affection in public without some degree of fear. And the conservative feeds were all about terrorism and ISIS and domestic radicalization and the “clash of civilizations” and the fact that the liberals refused to call Omar Mateen an Islamic terrorist.

I remembered how I felt when Orlando happened. I was five months pregnant then. She might not even have survived on her own at that point. We were not yet two. And I woke up early that morning to her moving inside me and, unable to fall back asleep, I read the news and learned that a 29-year-old man had walked into the Pulse nightclub in Orlando and killed 49 people before he was shot by police. I had just come back from living in Orlando for the winter. I had its warmth and strip malls on my skin, in my breath, still. And I was crying before I even realized I was crying, tears that felt like they never began anywhere, but have always been there, at the lip of my eyes, waiting.

When I saw that infographic about Facebook feeds, the sadness was similar to what I would later feel after the election. It is the kind of sadness I imagine you might feel for a lost limb, or for the baby inside you whose heart has stopped before she really ever started becoming. In the days after the election, there were new Facebook feeds, new stories. “Make America White Again” and “Go Home” spray-painted on cars and walls. A man threatening to light a Muslim woman on fire unless she removed her hijab. Students or friends or friends of friends who were afraid to go out in the world, to go to school or even a convenience store. And then there were the celebrations: that man yelling at all the passengers on a Delta flight from Atlanta to Allenton, PA, “He’s your president, every goddamn one of you. If you don’t like it, too bad.”

We never really own our country, not like we think we own ourselves, these shimmering bodies that hold us. Before the birth, what I had was a belly. It was beautiful and round and I liked to place my hands on it and rub. I rubbed because I loved the way I was expanding and I wanted to feel my expansion as well as see it. It was mine. Until it wasn’t.

This country is still mine, as much as it never was. We were of two minds—another expression that makes little sense. But it is true that there are some of us who are scared and who feel calmer when he tells us that he will protect us, assures us that there is a clear enemy. Just over the border, just across the ocean, right here next to you. Beware.

I go today to see a radiologist. I found a lump while breast feeding. Because in breastfeeding you end up touching your breasts more than you normally would and one morning when I was kneading my breasts to see how full with milk they were, how much they would produce for this little being who needs me to live, I came upon the smallest of nodes, but a definite node, within the tissue. And in the weeks since it’s gotten bigger and I have an appointment today to find out if it might kill me.

Or if it’s benign: a word that’s always sounded to me exactly like what it means. No Harm. No need to fear. Today I will find out if that part of me is or isn’t of me. I imagine if I could summon up a god again, I might feel less afraid.

Instead, I will finish writing this. This coda of sorts. Coda from the Latin word for tail. At the end of One Hundred Years of Solitude, a child is finally born with a tail, fulfilling the matriarch’s original fear. She worried that one day her family would become too close, so close that they could no longer separate brother from sister from husband from wife, person from pig. And as is the case with all fears, hers eventually manifests itself.

That apple I mentioned before: I hadn’t realized that it would lead us to Eve. We could follow it to Newton: it was falling after all. But the thing I like about Eve is that, in the story of the beginning of everything, it was she who gave us pain during birth. I want to thank her for that.

This is not pretty. But I am here to see it.

I have given up a dog and a home and a past and a country and a tiny fetus that might have been a baby. And I have gained a new home and a partner and a child and then another child and also a new life. Once I was sitting on a dock looking at the tanned feet of my best friend while Florida’s sun beat down on our backs. Everything I owned has since been lost. Even my memories are not the same. I can’t know how long that round node in my breast has been mine. Maybe forever. My grandmother found a lump after dreaming that she would and waking and there it was. As much as I try not to be my mother, I am.

And these little ones. Ours. Mine. How long will it take until I give up and admit that none of anything I so badly want to own belongs to me. Least of all this fleetingly small and insignificant life.

Sarah Viren is a contributing writer for the New York Times Magazine and author of two books of nonfiction. Her essay collection Mine won the River Teeth Book Prize and the GLCA New Writers Award and was a finalist for a Lambda Literary Award and longlisted for the PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay. Her memoir To Name the Bigger Lie was a New York Times Editor's Choice and an NPR and LitHub book of the year in 2023. A National Endowment for the Arts Fellow and a National Magazine Award Finalist, Viren teaches in the creative writing program at Arizona State University.