“History of the Miserable Octopus” and Three Other Shorts

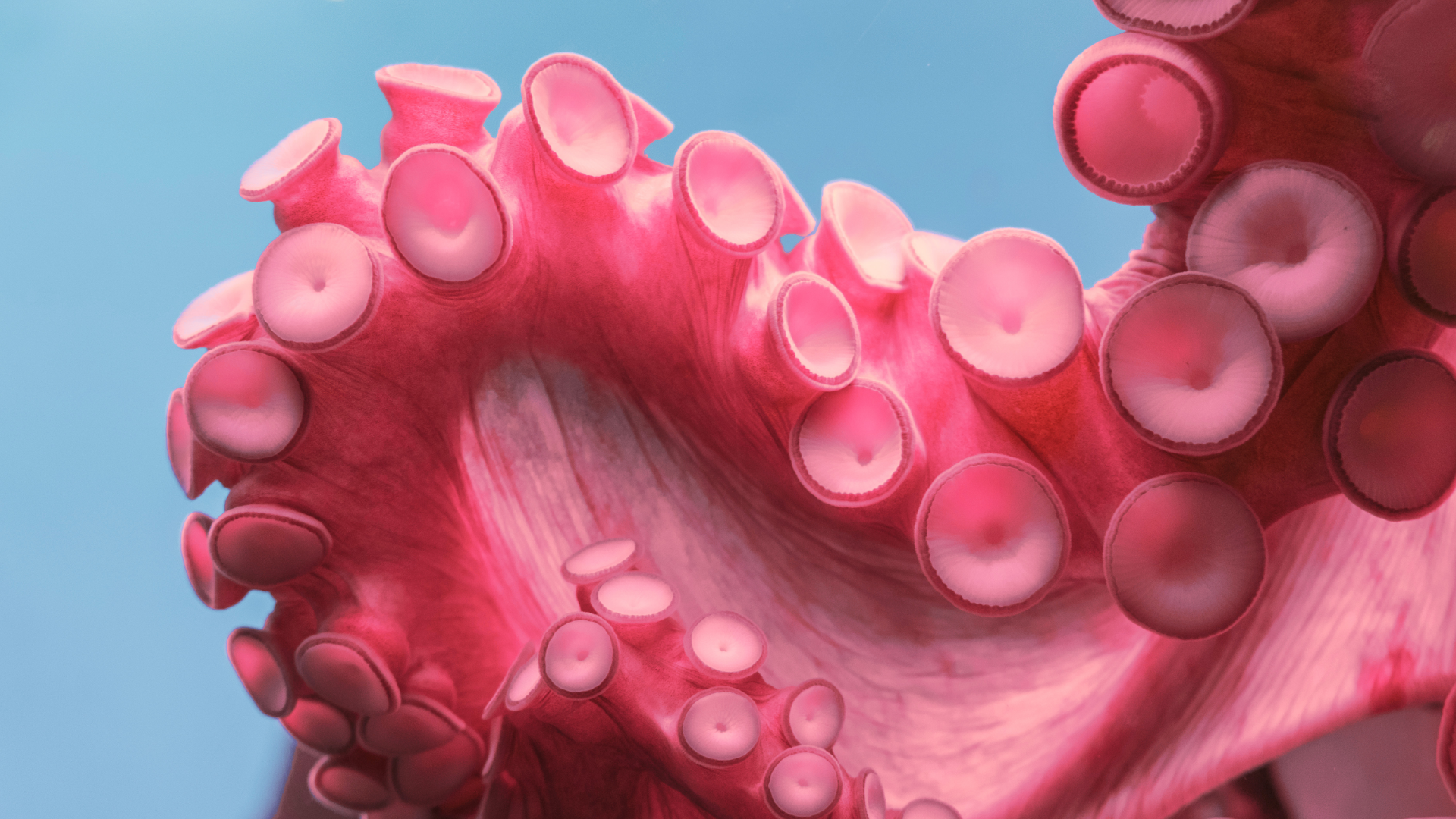

Image licensed through Adobe Stock. Edited.

Their Beauty was the Envy of the Neighborhood

I jimmied my neighbor’s window, tossed the man over my shoulder and hauled him out the front door. A light breeze blew ashes across the lawn. A dark figure carrying a bundle over his shoulder crossed my path, so I was not surprised to find my own bed empty, and my dear husband’s spot still warm. My neighbor’s husband hid under the piano, shivering. I pointed to the open door. I’d made my point. But he didn’t go.

For the first few days, he slept in the closet, like a squirrel. It must have made him feel safe. I left a bowl of mixed nuts, which were gone in the morning. One night he scratched at my bedroom door, on all fours. I let him in. He grew on me. He came so hard I called him Euphrates. I decided he could stay. In his sleep he groaned, “I love you so much.” “Who?” I said. “You,” he groaned. “You who?” I said. “You,” he groaned, and so on.

A scorpion climbed out of his mouth. It skittered off the bed, out the door, toward the baby’s crib. Indeed, I’d underestimated my neighbor.

History of the Miserable Octopus

Once, an octopus—many-hearted, hive-brained, boneless, muscular as a cloud—constructed a human form out of cheap materials that he knew would fall apart after eighty years at the most. He floated down into the human body to begin his adventure.

But in the new clumsy frame he struggled to move, like a novice puppeteer: his tentacles maneuvering the two ungainly arms, planks hinged in the middle. And his multitudinous mind that knew the restless ebb and flow of watery prairies labored to comprehend this world of dry cumbersome objects.

His brothers hissed and clawed him as he walked by, laughing. His teachers stared pitilessly from their big desks, rarely speaking.

He loved his mother so much. As she watched TV he reached to hug her and broke a lamp and his mother shouted. She kept shouting. He couldn’t calm her down.

He finally just hid in his room and shot ink at whoever walked by.

His schoolmates teased each other so well. He watched in admiration. He tried in vain through camouflage and mimicry to tease as they did, but his mind was murky, muddy.

He had a painful longing to be an octopus again, though he couldn’t put into words what that was.

One day in front of his house boys were teasing a tomboy named Cindy. They had one of her roller skates. She was rolling herself in a kind of sad circle with her sock foot. They gave her skate to a pit bull, which walked off with it through a hole in the fence.

He sat with Cindy as she slowly unlaced her skate. Neither of them said anything. There were so many laces, it took a very long time. The sky changed. It started to rain.

He married Cindy and loved her so much but his tiny brain, which processed the infinite as a series of dualities, wanted to possess her. His jealousy made her angry. When they argued his mouth shot ink everywhere, in a messy cloud. She left him, he died alone.

Death was a happy event. At last he cast off the heavy frame and shot outward in his true octopus body—hardly a body at all, like fire into fire—to return to the sky.

Hyperconsciousness Song

After answering phones all afternoon at a suicide hotline, I walked the city streets, limping slightly, as I used to as a kid, the way my uncle Hubert, the one with Perthes, used to limp. Children drifted by on skateboards, scars on their faces, salamander-pale.

Orange cotton-candy light.

A smell of chemical flowers, the red sun dangled over the hatmaker factory like the Hindenburg.

A magnificent prostitute burst out of a green door, adorned in finery, necklaces, in tall purple shoes, she locked step with me, limping a bit, like me, an old ritual of ours, some wordless intimacy. We stopped to look at the palm of a broken window, threshold between worlds.

Was she my mother? I was born here!

How to Survive a Long Distance Relationship

“My darling,” I said, in one of our many long-distance phone calls, “have you been true?” “Oh yes,” you said, “though a man sometimes helps me put on my panties.” “Pardon?” I said. “He’s just a jazz drummer,” you said. I coughed. Just! But who could blame you? His rhythm. The sheer wrist speed. I imagined, within the jazz drummer, a whirring, as within the Enola Gay or a death’s-head moth.

My librarian friend answered her door wearing the V-neck sweater I liked. She removed my sneakers and licked my toes, while recounting curious facts she’d read at the library. “In 1567,” she slurped, “the man with the longest beard in history perished while fleeing a fire, tripping over his beard.”

“Why,” she said, “are you tapping a beat on my goddamn head with your fingers?” “I’m not!” I wept, running out the door.

I ran and ran in the rain. I thought, Yes, yes, she’s right! I have been tripping over my beard my whole life.

John Wall Barger is the author of six collections of poems and one critical collection, The Elephant of Silence: Essays on Poetics and Cinema (LSU Press, 2024). He’s a contract editor for Frontenac House, lives in Vermont, and lectures in the Writing Program at Dartmouth College.